Closing the gap: On the road to terahertz electronics

Closing the gap: On the road to terahertz electronics

Asymmetric plasmonic antennas deliver femtosecond pulses for fast optoelectronics

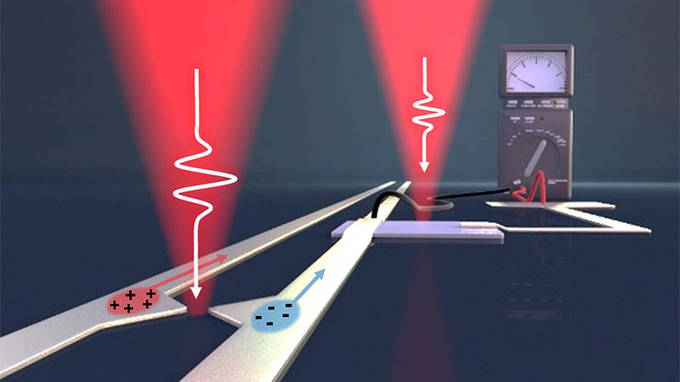

Pulses of femtosecond length from the pump laser (left) generate on-chip electric pulses in the terahertz frequency range. With the right laser, the information is read out again. – Image: Christoph Hohmann / NIM, Holleitner / TUM

Classical electronics allows frequencies up to around 100 gigahertz. Optoelectronics uses electromagnetic phenomena starting at 10 terahertz. This range in between is referred to as the terahertz gap, since components for signal generation, conversion and detection have been extremely difficult to implement.

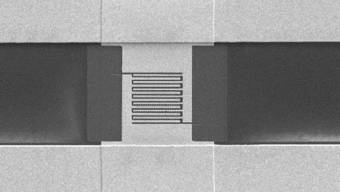

The TUM physicists Alexander Holleitner and Reinhard Kienberger succeeded in generating electric pulses in the frequency range up to 10 terahertz using tiny, so-called plasmonic antennas and run them over a chip. Researchers call antennas plasmonic if, because of their shape, they amplify the light intensity at the metal surfaces.

Asymmetric antennas

Electronmicroscopic image of the chip with asymmetric plasmonic antennas made from gold on sapphire. – Image: Holleitner / TUM

“In photoemission, the light pulse causes electrons to be emitted from the metal into the vacuum,” explains Christoph Karnetzky, lead author of the Nature work. “All the lighting effects are stronger on the sharp side, including the photoemission that we use to generate a small amount of current.”

Ultrashort terahertz signals

The light pulses lasted only a few femtoseconds. Correspondingly short were the electrical pulses in the antennas. Technically, the structure is particularly interesting because the nano-antennas can be integrated into terahertz circuits a mere several millimeters across.

In this way, a femtosecond laser pulse with a frequency of 200 terahertz could generate an ultra-short terahertz signal with a frequency of up to 10 terahertz in the circuits on the chip, according to Karnetzky.

The researchers used sapphire as the chip material because it cannot be stimulated optically and, thus, causes no interference. With an eye on future applications, they used 1.5-micron wavelength lasers deployed in traditional internet fiber-optic cables.

An amazing discovery

Holleitner and his colleagues made yet another amazing discovery: Both the electrical and the terahertz pulses were non-linearly dependent on the excitation power of the laser used. This indicates that the photoemission in the antennas is triggered by the absorption of multiple photons per light pulse.

“Such fast, nonlinear on-chip pulses did not exist hitherto,” says Alexander Holleitner. Utilizing this effect he hopes to discover even faster tunnel emission effects in the antennas and to use them for chip applications.

Source: https://www.ph.tum.de/